Two-time Stanley Cup winner Daniel Carcillo was nicknamed “Car Bomb” for his violent performance on the ice, an explosive reputation that resulted in seven diagnosed concussions, as well as hundreds more that he suspects he had. After over a decade of therapy, multiple stints in rehab and hundreds of thousands of dollars spent on traumatic brain injury (TBI) treatments, his hopelessness left him suicidal.

“My life was perfect from the outside, and I knew it, but I still wanted to kill myself,” says Carcillo, who retired in 2015. “So I started to make plans to unburden my family.”

He sought out psychedelics as a last resort. After years of self-experimentation with psilocybin, ayahuasca, 5-MeO-DMT, non-psychoactive cannabinoids and adaptogen supplements, he landed on a multimodal approach of intermittent psychedelic journeys paired with a daily brain-health regimen to reinforce recovery.

“Nothing gets fixed in five hours,” he says of full psychedelic trips. “You can shift perspectives, which is awesome, but microdosing helps solidify the new neural pathways activated during a psychedelic experience.”

Two years later, he credits this routine for the fact that his brain imaging and blood work routinely show up clear.

Carcillo is now the CEO of Wesana Health, a company he founded in 2020 to develop novel TBI treatment solutions, including psychedelics. (The company recently made waves when it was announced that Mike Tyson came aboard as an investor.) Once known for his uncontrollable anger as a Blackhawks enforcer, Carcillo now rarely strays from his Zen temperament when candidly discussing his past. His tone only switches to impassioned when asked about his company’s mission.

“How am I going to bring a veteran who is making [suicide] plans to this medicine?” he asks. “[Or] help a mom whose kid knocked himself out playing at the park? We have to deliver this method to TBI survivors through a standard-of-care regimen. I will not waver from that.”

Traumatic Brain Injuries: A Silent Epidemic

Millions suffer traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) each year in the United States alone, and suicide is the leading cause of death amongst TBI survivors. Read that again. People with multiple concussions and head impacts—often athletes and veterans—are at increased risk for behavioral, physical and emotional dysfunction.

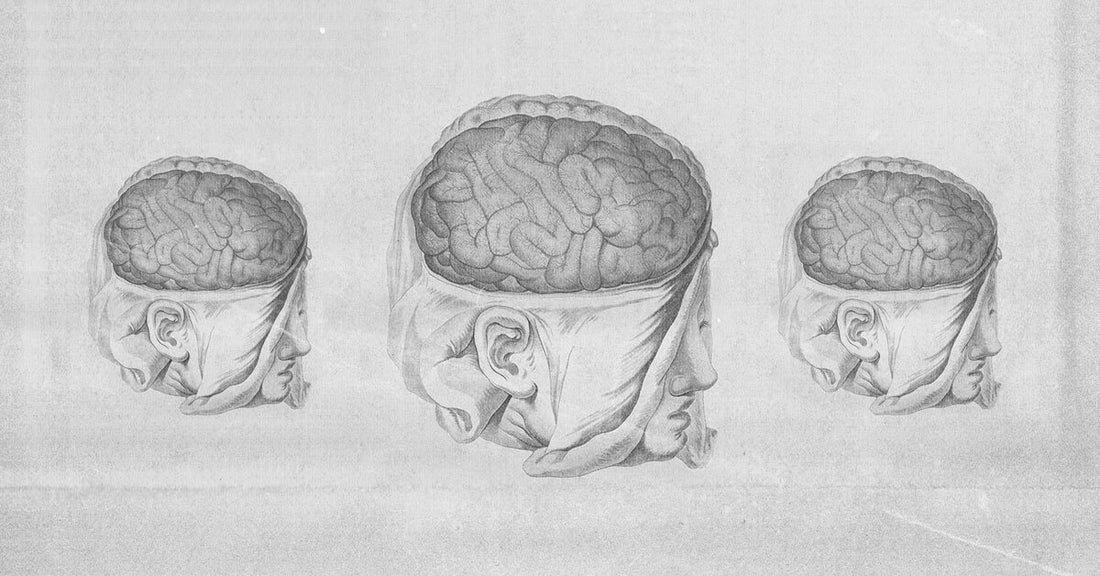

A TBI will increase neural inflammation over time, which affects hormone production. When hormones are out of balance, emotions are out of balance, and this leads to adverse psychiatric symptoms including depression, insomnia and mood swings. The symptoms can start years after the TBI occurs, and the overlap of symptoms with other mental illnesses, such as PTSD, often leads to misdiagnosis. Repetitive TBIs are linked to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

There’s an image crisis in professional sports around head injuries, and research suggests that psychedelics can help. The UFC recently announced that it is “diving into” psychedelic research to treat brain issues in athletes. The statement followed the announcement of a potential collaboration between Johns Hopkins University and psychedelic research nonprofit Unlimited Sciences to research psilocybin for TBI.

The notion of treating TBI with psychedelics isn’t a shot in the dark. Dr. Martin Polanco has been treating patients with ibogaine, a potent Gabonese psychedelic plant, for over 20 years. His work with special-operations veterans led to the development of The Mission Within, where most of his work with ibogaine and 5-MeO-DMT to treat TBI is funded by nonprofit veteran organizations. A published study that surveyed 51 vets who completed The Mission Within program showed significant and very large reductions in cognitive impairment, suicidal ideation, anxiety, depression and symptoms of PTSD. Most participants rated the psychedelic experiences as one of the top five personally meaningful (84%), spiritually significant (88%) and psychologically insightful (86%) experiences of their lives. Now, Veterans Exploring Treatment Solutions (VETS, Inc.) is funding a 30-patient study at Stanford, where Polanco and Dr. Nolan Williams will study the effects of ibogaine on mild traumatic brain injuries (mTBIs).

How is Ibogaine Used to Treat TBIs?

“Addressing the neuroinflammation and hormone issues is one of the most important pillars in TBI treatment,” says Polanco, whose interest in this field originated with his own TBI from a motorcycle accident. Research shows that psychedelics regulate inflammatory pathways and activate the release of neurotrophic factors that promote the growth and differentiation of new neural pathways.

Dr. Joseph Barsuglia, a Veterans’ Affairs-trained clinical and research psychologist who consults at The Mission Within, describes these pathways as tracts that run through the brain. These tracts can experience micro tears after a brain injury that are often not visible on common brain imaging. This is even the case with mTBIs, where someone doesn’t lose consciousness but may temporarily become confused or see stars.

“Ibogaine has a very broad spectrum of effects compared to other psychedelics and binds to over 50 neuroreceptors, which increases energy metabolism in the brain and allows for a cognitive ameliorating and enhancing effect,” Barsuglia says.

He recounts observational ibogaine studies in which participants reported a physical sensation in their brain tissue akin to it being “scrubbed like a toothbrush” or having a “brain transplant.” The experience lasts upward of 24 hours and often brings on sensations of intense physical discomfort. Dizziness, nausea and purging are common.

Barsuglia and Polanco validate any wariness that may arise from these accounts and encourage patients to try other treatment options first. Ibogaine has a riskier safety profile than other psychedelics, and reputable treatment centers are few and far between. Barsuglia also points out an ethical dilemma.

“Ibogaine’s increasing popularity [in the West] has threatened its availability to the Bwiti indigenous people of Gabon,” he says, “and the lack of sustainable supply presents a massive moral and ecological issue.”

Several patents on ibogaine treatment have been registered with the intent to commercialize, with little to no giveback to the communities that have cultivated sacred knowledge of these medicines for thousands of years. “One view in Bwiti is that there should be a tree planted each time a person takes iboga, and this is an absolute bare minimum for ecological reciprocity,” says Barsuglia. “Are these new corporate psychedelic pharmaceuticals who are scaling ibogaine and its related molecules planting iboga trees while they secure their next round of funding? We have an ethical and legal duty to demand reciprocity for what has been extracted from the indigenous people.”

But when looking for healing, one doesn’t necessarily need to use a fire hydrant to put out a candle. Polanco recommends a multimodal evidence-based approach that integrates anti-inflammatory and neuroregenerative modalities, including meditation, yoga, sleep hygiene and diet. “Ibogaine should be the last resort,” he says.

He also emphasizes the importance of emotional integration. He likens ibogaine visions to a filing cabinet, where lifelong memories are sorted like a computer being defragged and, therefore, working more efficiently afterward. This helps individuals review and integrate difficult early childhood trauma, which can compound the effects of a TBI.

“Oftentimes we’re not just dealing with physical brain trauma, but also complex PTSD with childhood memories that need to be processed,” Polanco says.

Like psilocybin and other psychedelics, studies show that ibogaine stimulates brain regions that are shut down due to trauma. Shutting down is your mind’s survival mechanism, which is wholly valid and necessary during and after a traumatic experience. However, it can reach a point where it no longer serves its purpose and manifests as hypervigilance. Psychedelics create a hyper-connected state in the brain, which may allow TBI survivors to access, process and integrate difficult memories.

Carcillo, the former pro hockey player, has experienced the emergence of buried traumas firsthand. The phenomenon is called TBI/PTSD polytrauma.

“Certain traumas came up with psychedelics that I didn’t even know were there,” he shares. “The abuse I experienced as a minor made me realize how traumatic events turned me into a product of my environment.”

He doesn’t look back fondly at how that made him act on the ice, but he’s made peace with it. “I wouldn’t be helping TBI survivors otherwise,” he says.

TBI and CTE: Know the Difference

When it comes to athletes and veterans, it’s important to note that suffering multiple TBIs and having CTE are correlated—but not the same. With CTE there is a specific dysfunction with a neural protein called “tau” that leads to neurodegeneration. There is no treatment for CTE and it can only be definitively be diagnosed after death via brain tissue analysis.

Until then, any CTE “diagnosis” in the living is a suggestion based on assessments that overlap with TBI. With athletes and veterans, however, the terms are casually used interchangeably—an assumption that Carcillo asserts is irresponsible. Labels are stigmatizing, and a label as dramatic as CTE may worsen a TBI survivor’s mental state. “It is extremely debilitating to think that you might be living with neurodegenerative disease,” he says.

He himself was debilitated by those thoughts, and credits ayahuasca with releasing him from the fear of CTE that held him back.

While the personal accounts are compelling, we can’t assume psychedelics are mental health panaceas without more research—especially when it comes to treating conditions as complex and elusive as TBI and CTE. Until then, Carcillo aims to empower TBI survivors by putting them in touch with their innate ability to heal themselves.

“Framing is important, and brain injury symptoms are something you can recover from,” he says. “One of the most important aspects when embarking on the healing journey is to shift the perspective of the injury and ensure that the TBI survivor has the right mindset.”

Dorna Pourang is a psychedelic researcher and clinical trial leader at MAPS PBC. MUD\WTR donates a percentage of its earnings to MAPS. Any statements are the personal opinion of the author and do not necessarily represent the opinion of MAPS or MAPS PBC.