“My sister, my sister!” the girl called. She led Jon Rose through the humid refugee camp. They walked down dirt pathways and through the destruction, the sort that kills tens of thousands of people in seconds, shaking physical and mental landscapes alike, forcing survivors to dig through neurological rubble for years to come.

Haiti, January 15, 2010. Days after the 7.0 magnitude earthquake.

In the wake of the tremor, Rose had come to Haiti as a volunteer. His immediate job was to visit refugee camps and find people in need of medical assistance.

Rose followed the girl deeper into the camp. They ducked into her “tent,” a tarp with sticks for scaffolding and bedsheets for walls. Sitting on the ground was the girl’s sister, a single crutch at her side. “She was probably 18,” Rose recalls. “Just beautiful. She had almond-colored eyes, a green top, denim skirt and cornrows that fell down to her shoulders.”

Then, Rose saw the wound, stretching from her knee down to her foot and so deep he could see infected tendons and white bone. It had gone gangrene. Rose advanced, but the girl recoiled. “Don’t touch me, they’ll take my leg!” she shouted. In Haiti, amputees are shunned.

A world away from his home in Laguna Beach and his career as a professional surfer, Rose knelt down and said with resolve, “They’re not gonna take your foot. I promise, I promise.”

The girl allowed Rose to take her. She wrapped her arms around his neck and climbed on his back, and he piggybacked her a half mile to the medical tent. As soon as the doctors saw her injury, they rushed her into surgery.

The following day Rose was back in the medical tent. The girl was out of surgery, a bandaged nub where her leg had been. “You lied to me!” she shouted.

Rose walked out of the tent and never saw her again.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

A few months before the earthquake in Haiti, Rose had already made the decision to deliver portable water filters to places in need, just on a smaller scale. While on a surf trip to the Mentawai Islands in Indonesia, he brought 10 water filters that he planned to deliver to a rural community in Sumatra, a pet project taking after his old man, who had delivered water filters in Africa years before. While on the boat, a 7.6 magnitude earthquake rocked the islands. Rose asked the captain to take him ashore where he implemented the filters to survivors within local relief centers. It was amidst this wreckage that he uncovered an important quality about himself: The more chaotic the situation, the calmer he became.

This experience cemented Rose's nagging feeling that he couldn't be a dilettante humanitarian: He had to commit. Which meant he was destined to witness some truly ugly human trauma, thus putting his psyche at risk. Although he's told this story to scores of journalists, this is the first time he's talked about his own mental scars and what he's recently done to heal them.

Rose expected to volunteer in Haiti for two weeks following the earthquake. Two years later, he finally went home. “I gave up pro surfing because at that point the other guys were better than me,” he once said during a TV interview. “Maybe I could have milked it a little longer, but I’m a realist.”

It was in Haiti that he developed the chops to eventually start his nonprofit, Waves For Water, a special ops–style group that provides clean water solutions, such as water filtration systems, in disaster zones and developing communities around the world. Actor Sean Penn heard about Rose's work and offered to help fund his efforts. Over the past 10 years they have implemented clean water programs in 48 countries, bringing filtered water to nearly four million people.

During that time, Rose has witnessed “dozens” of situations as intense as the one with the Haitian girl.

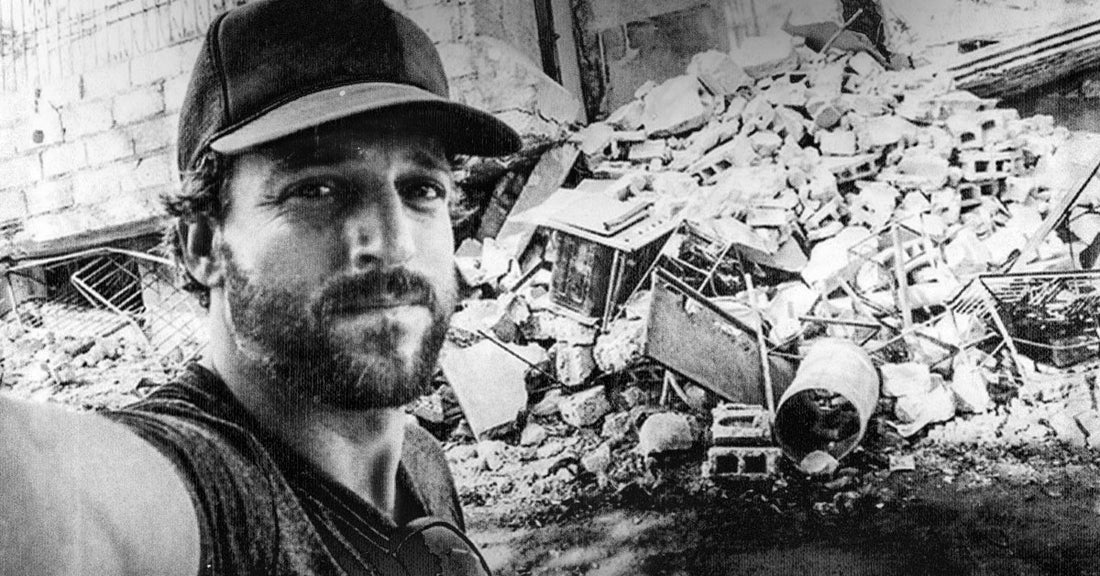

Rose demonstrating one of his clean water filters

Rose demonstrating one of his clean water filters

Rose, now 43, looks a bit like an aging fighter jet pilot: athletic build, strong jawline and graying stubble. When talking about his trauma, he does so in compact sentences, like he’s teaching someone how to give CPR. Rose prides himself on being tough. “My gift is that I can handle and process pain greater than other people.” Until recently, he could count on one hand the amount of times he cried. “I don't know if that’s necessarily a good thing, but it’s just true.”

Somewhere along the way, tectonic plates in his mind began to shift. The first concerning incident was on the corner of Prince and Broadway, a busy intersection in New York City, where Rose lived for a number of years. Less than 24 hours prior, he had been in Afghanistan, hearing the Black Hawk helicopters roar overhead as he and his team implemented clean water solutions. Now, he was here. This mental schism caused a feeling of total dissociation, like he was encased in a yolky shell of numbness. Amidst the honking cars, tall buildings, and the gun metal gray winter sky, he turned to a woman and asked, "Excuse me, can you see me?"

He shared the incident with a few close friends, to which one responded, "Of course you're fucked up, look at all the shit you've seen." Although the friend was likely just trying to help, Rose cemented the narrative that he must be “fucked up,” and always would be. From that point on, every shift in mood carried the weight of this new narrative. Jon Rose: The man who stayed calm under pressure, with an identity built on thriving in heavy situations … it all began to unravel.

Then, he heard about MDMA-assisted therapy on some popular podcasts and got curious about its potential to help him.

MDMA and the Brain

Enter Rick Doblin, the psychedelic activist who uses MDMA, or the street drug known as ecstasy, in conjunction with therapy to treat soldiers suffering from acute Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Doblin founded the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic studies (MAPS) in 1985 with a singular vision: To use psychedelic-assisted therapy as a tool to treat the myriad mental health issues our society collectively faces.

Working against cultural stigma and a maze of regulations, many onlookers saw Doblin’s efforts as quixotic, but now—nearly 40 years later—the new psychedelic revolution seems to have achieved liftoff. In interviews, Doblin is a palpably genuine dude, with wild, frizzy hair and an easy laugh. These days, he has reason to be happy, as media ranging from The New York Times to The Joe Rogan Experience have nothing but good things to say about the potential of psychedelics to heal.

In an interview, Doblin explained how PTSD impacts the brain and affects the lives of about 15 million Americans per year.

“PTSD reduces activity in the frontal neocortex, where we think logically,” he says. “It also causes hyperactivity in the amygdala, where we process fear.” So when something unrelated triggers the painful memory, say a slamming car door, the person relives the trauma with vivid presence. “They can become so subsumed by the past that they’re no longer living in the present,” he says.

The pharmacodynamics of MDMA work by reducing activity in the amygdala so people can inspect their memories without the rush of fear. The drug also increases connectivity between the amygdala and the hippocampus, where we store long-term memory. This allows the brain to see the memories in the rear-view—rather than continuing to loop them in the present. After MDMA therapy, people tend to have clearer memories of their trauma, but they don’t carry the same emotional valence. MDMA also induces oxytocin, known as the love hormone, which allows people to accept themselves within the context of their trauma. “If I had to condense MDMA down to one thing,” says Doblin, “it’s that it can offer self-acceptance.”

In May 2021, the journal Nature Medicine published the results of the most advanced trial of psychedelic therapy to date. In their Phase 3 trial of MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD, 88 percent of participants who received MDMA in conjunction with trauma-focused therapy experienced a clinically significant reduction in symptoms. Two-thirds of participants no longer met criteria for a PTSD diagnosis, and a number of participants reported MDMA-assisted therapy helped them address the root cause of their trauma for the first time.

One veteran said, “PTSD changed my brain and MDMA changed it back.”

MDMA is currently a Schedule 1 drug, and if all goes well with the clinical trials, the earliest it could be approved for therapeutic use by the FDA is at the end of 2023. Which is why, when Rose decided to try MDMA therapy, he would first need to find an underground sitter who would be willing to accompany him during the session. Since the drug was criminalized in 1985, thousands of people have gone this route.

The MDMA-Assisted Therapy Session

Mikalah (not her real name) is a therapist who conducts sessions using a similar protocol to MAPS. "MDMA-assisted therapy can help us both get out of our own way and drop into something inherent within ourselves," she says. "My job is to make sure that I’m as empty a vessel as possible, while making sure that I’m giving all of the support and resourcing that they need.” Doblin also highlights the cost-effectiveness of this therapy, “If you have the preparation, experience and the integration, then you can make really long-term changes with a relatively short-term intervention.”

Prior to the session, Rose had already been working through his trauma using Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), a form of psychotherapy where a person is asked to recall distressing images. The therapist then directs the patient with bilateral eye movement. As strange as this therapy sounds, it’s included in several evidence-based guidelines for treating PTSD. “Working with Jon was particularly special because he had already done a tremendous amount of self-work going into it,” recalls Mikalah. “The house had good bones, so to speak.”

Rose was initially uncertain about going public, but now he hopes his account can help more men open up about their trauma and de-stigmatize MDMA-assisted therapy.

They started the session in the afternoon. There was a burgundy couch, blankets and a view of a swaying coastal forest. He took the capsules with a glass of water, lay back, covered his face with the eye mask and the trip began.

He was back in Haiti, standing at the bottom of a hill, squinting up through the slanted light. He spotted a silhouette meandering down the hill. It was a local woman carrying a bowl on her head. When she reached the bottom of the hill she walked straight up to Jon until she was less than a foot away from his face. They stared at each other for a long moment. Then, she reached into her bowl, held out an orange peel, and placed it in his hand. She motioned to put the orange peel to his nose: It helped cover the stench of dead bodies. But rather than horror, he saw divinity. The gratitude, the fucking graditude. It swallowed everything like a sun, radiated out of him and touched every aspect of his life story. He thought of the friendships he had foraged and the organization he had built. Then, the spotlight of his attention zoomed back to Haiti, this time in the refugee camp. He was standing in the girl’s tent. Her green top, her almond eyes, the infected wound.

“I was put there.

I did the best I could.

And that's enough."

Kyle Thiermann is MUD\WTR's Head of Editorial and host of The Kyle Thiermann Show podcast.