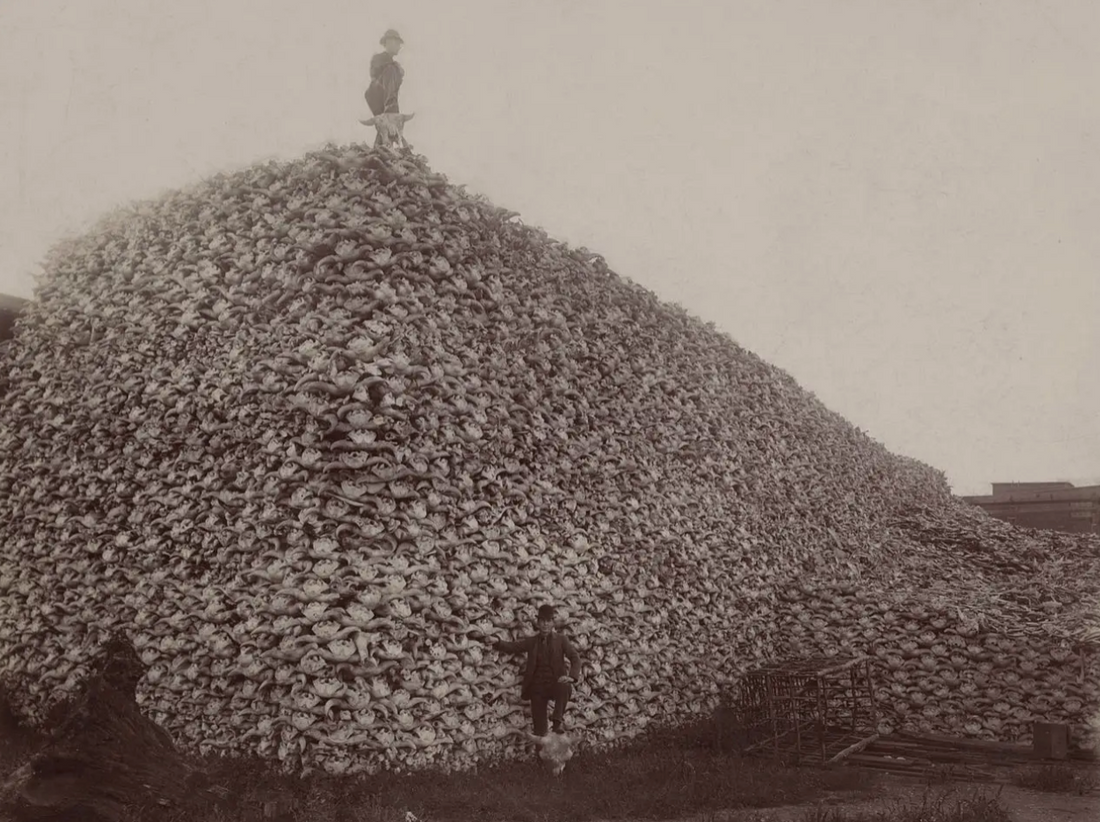

An iconic photograph can define an era through the story it tells. The twin towers collapsing. The first photo of the Earth from space. A lesser-known photograph shows how humans nearly brought bison to extinction in the early 1900s.

It’s a black and white image of bison skulls piled four stories high like a snowy mountain. Around the year 1900, a combination of commercial incentives and a strategy to starve Plains tribes had reduced more than 60 million bison to a remnant herd of fewer than 300. The book Rifle in Hand details the story: “The great American Plains fell deathly still,” writes author Jim Posewitz. “The grunts and roars of the bison that played across the Great Plains for 15,000 years were gone.”

Today, bison in North America have rebounded to around 500,000 and many other endangered species have come back, as well, due to policy changes brought about, and carried on, by hunters and conservationists.

I had been exploring the Montana wilderness for several months by the time opening week of elk season approached in early September. I was eager to hunt with the locals, and snagged a rare access pass from a Missoula local named Dylan Snyder, who invited me to join him for a three-day camping and hunting excursion in southern Montana.

Dylan is a lifelong hunter, an avid river surfer, and works for a nonprofit called Backcountry Hunters and Anglers. A gregarious former oil and gas worker named James is with him when I arrive at camp. Dylan instructs me to remove my California license plate and screw on an expired Montana plate so my RV doesn't get fucked with by locals. The prejudice is understandable: Californians roll into town and jack up property prices. “A lot of Montanans don’t have much money,” James tells me. “What we do have are our public lands.” With my new license plate safely screwed on, we walk into the woods with bows in hand.

On the first morning, we walk up a trail for a couple of miles and sit in a forest of thin, grey lodgepole pines while James blows into a horn-shaped gadget and begins to bugle, hoping to lure our elk into sight. Elk organize in harems. Bugling signals to a male elk, known as a bull, that another bull is on his turf, and it can coax him to the hunter. Nothing. James mimics the sound of a female elk, known as a cow, using a small diaphragm inside his mouth. It’s higher pitched and more whiny than the sound of a bull. Nothing. We move to the top of the mountain known as the “bench.” James calls again over the overwhelming expanse of public lands.

Hunters directly benefit from conservation through a number of ways. The first is The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation, which was pushed forward by hunters around the same time bison were on the verge of extinction and is probably the greatest environmental achievement in the history of humankind. The model rests on two basic principles: First, wildlife is for the non-commercial use of all citizens. Second, wildlife should be managed to maintain optimum population levels to ensure healthy ecosystems forever. In a world where many lawmakers and extractive companies see nature as nothing more than a commodity to be chopped and sold, the concept of preserving vast swaths of land and wildlife for the public to access is revolutionary. In America, you have free access to enjoy hundreds of millions of acres of land, because you own it. This is in contrast with much of Europe, where hunting is reserved for those who can pay hefty sums to chase animals on private land.

Back at camp, Dylan and James talk often about Teddy Roosevelt. Our hunter president, who impacted the American landscape by pushing forward this conservation model. While in office he designated 18 national monuments, including Niagara Falls and the Grand Canyon, establishing 51 bird sanctuaries and the U.S. Forest Service. By the time he left office, Roosevelt had set aside 230 million acres for public protection. No president, before or since, has done more for conservation.

Although public lands are free to access, it does cost money to hunt. In most places there are strict limits on how many animals one person can hunt to ensure that their populations stay at healthy levels. Tags, which are licenses to hunt an animal, can cost anywhere between a few bucks to a few thousand bucks depending on the species. That money goes directly back into conservation.

Public land can be expensive to maintain. Dirt roads, wildlife biologists, controlled burns—it all takes money. Funds come from various sources, but one is from the clothes Dylan, James and I are wearing. The Pittman Robertson Act was pushed forward by hunters and passed in 1937, placing a 10-percent tax on hunting gear, including camouflage, guns, and ammunition, to be used to fund conservation. So many gun-lovers purchased firearms during Barack Obama's presidency—out of fear that they would be banned—that some conservation groups called the resulting revenue "Obama money." While many environmental causes rely solely on generous donations, hunters have set up a system where participants are funding conservation as soon as they start buying equipment. It was once suggested that the broader outdoor industry adopt a similar tax, known as the “backpacking tax,” but it never came to fruition.

On Aug. 4, 2020, public lands saw its biggest win in nearly 100 years. In a deeply polarized nation, both democrats and republicans voted to pass the Great American Outdoors Act, allocating nearly $10 billion toward public lands infrastructure. It also guarantees that Congress will spend $900 million through the Land and Water Conservation Fund. The funds are being taken from oil and gas drilling currently operating on public lands and waters. As a lifelong surfer, I was curious if these funds benefit ocean-goers as well. I spoke to Chad Nelson, CEO of Surfrider Foundation, and asked him about it. “Surfers benefit hugely,” he said. Part of that $900 million goes to coastal state parks such as San Onofre, home of the famous Southern California wave called Trestles. Although every hunter I have spoken with in Montana knows about this act, I've found that far fewer surfers are aware of it. Perhaps I wouldn't have heard of it, either, if I weren't here in Montana among the hunters.

The only animals I think much about when riding waves are the ones that can eat me. The sounds of an otter cracking a shell with a rock or a swooping pelican enhance the experience of surfing, but they are not a necessary component. But for a hunter, an animal is the wave, and they want to keep the session going.

At 4:30 a.m. the next morning, I sloth my way into James’ car and we drive up dirt roads to bugle from a different spot. We had still not seen any elk. We watch the sun peek over the mountain, shooting her first rays of light like golden lasers across the valley. We use the OnX app to check property lines and determine if any sections of wilderness are on private land, making them inaccessible. To be a hunter is to be engaged in a constant battle of private interests incessantly trying to buy public land. What’s more, there are 6.3 million acres of public land that cannot be accessed because they are encircled by private land. We hunt all day and come up empty handed.

On the final day, we bugle and get a few calls back from a bull elk, but after playing a long game of “who can stay quiet the longest,” the bull wins and the largest animal I see on my first elk hunt is a squirrel. But it was a big squirrel.

We may not have bagged an elk, but I didn't feel like I was walking away empty handed. Over those three days, I came to see the hunt as an educational opportunity. As I flail my way into this new world of hunting, I’ve decided not to make animal kills my primary metric for success or failure. Instead, my goal is to notice more every time I’m in the wilderness, and this includes learning about, and having respect for, the systems that hunters like Teddy Rosevelt implemented that allow me to enjoy the great outdoors.

By: Kyle Thiermann