Sitting in my windowless office in Midtown Manhattan one day in the mid-1980s, I received a call from a Spanish journalist named Katalina Montero Alverez. She was in town and wanted to write an article about the Diamond District, where I managed a couple of buildings. She was told I might be willing to show her around. When she walked into my office the next day, all tight jeans, red cowboy boots, and flowing Spanish hair, I was suddenly very willing.

In the end, we showed each other around. I told her stories about how things worked on 47th Street, and she told me stories about her travels. At 32, she was only five years older than me, but her travels made me feel like a rocket that had lingered on the launch pad for way too long. That evening, over Mexican food, she showed me photographs she’d taken in the Philippines, Guatemala, and in Varanasi, along the Ganges. By the next morning, I’d decided to quit my job, give away my possessions, and buy a one-way ticket to India. Launch sequence had commenced.

I had $15,000 saved. I’d heard that you could get a better exchange rate in Asia with cash than traveler’s checks, so I bought a money belt and packed it full of crisp $100 bills. One hundred and fifty Benjamins was plenty to fund my travels for several years in Asia.

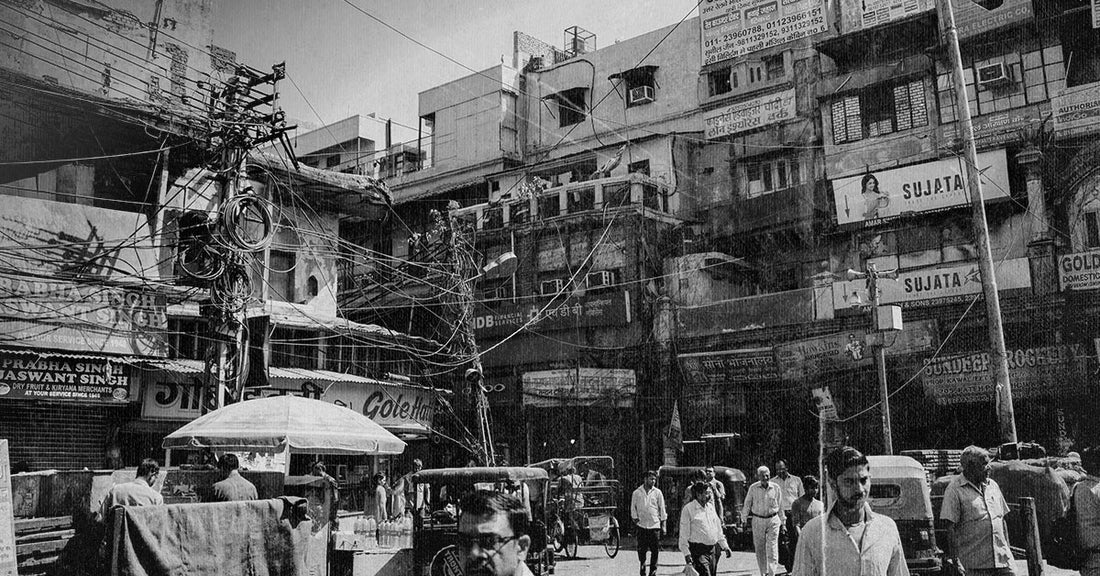

A few weeks later, I landed in New Delhi late on the last night of the Diwali festival. In the taxi from the airport, I saw spent fireworks everywhere, but I hardly noticed, because everything about these streets amazed me: the damp olfactory chaos ranging from curry to cowshit; the sleeping people huddled along sidewalks and roadsides, soundly slumbering just a few feet from the passing tires of buses and ox-carts; the cows, elephants, and camels clomping calmly along between trucks, bicycles, and hurrying pedestrians. And the colors. I’d never seen yellower yellow or redder reds—not even with pharmaceutical enhancement. It was overwhelming. It overwhelms me still, in memory.

The only still space in this roiling, marvelous mess—the eye of my personal Indian hurricane—was a small dark room I’d rented in a nondescript guest house near the train station, in Old Delhi. I'd chosen the place randomly, from my Lonely Planet guidebook. There were a thousand just like it offering a dozen or so rooms with damp, creaky beds, leaking, rusty showers, comically old locks on the doors that could be picked with a fingernail, and, crucially, a small balcony overlooking the endlessly fascinating street scenes. I was probably paying a dollar or so per night for the room. Because some other traveler had warned me about stealthy night-time thieves, I went to bed every night with my fat money belt tucked safely under my pillow, betting that nobody could separate me from my stash without waking me.

A week or so after my arrival in Delhi, I bought a ticket for the epic train trip to Kashmir, which left very early in the morning and wouldn’t arrive at its destination until a couple of days later. I packed up my gear the night before, set an alarm for 5 a.m. and went to sleep. When I awoke in the dark morning, I quickly dressed, brushed my teeth, shouldered my heavy backpack, and set off for the station, arriving an hour or so before the train was to depart. Plenty of time to get a cup of the sweet chai I was already learning to love.

Although the sun had hardly come up, it was already warm, and the weight of my pack had me sweating. Just as generals prepare for the previous war, I’d packed for my previous trip, which had been a long hitch-hiking excursion to Alaska. So I was probably the only idiot in all of India carrying 70 pounds of camping gear: a tent, sleeping bag, portable stove … absurd.

Sitting there in the train station, sipping my chai, waiting for my train to board, a single bead of sweat trickled down my spine. I reached around to the small of my back to wipe it and—Where’s my money belt?

I’d left it under the pillow.

Everything. My passport, two credit cards and every one of those 150 crisp hundred-dollar bills. Everything. Not robbed. Not cheated or tricked. I’d calmly walked away from an unlocked room in a very cheap guest house in Old Delhi in which I’d left everything. Years of anticipated travel evaporated in a second. Less than a week into my grand round-the-world odyssey, I faced the prospect of having to call my parents (collect) to ask for a loan to get myself home, to their basement, broke and broken.

I threw on my pack in a panic and took off running through the teeming, steaming streets back to the guest house. I must’ve been a sight. A skinny, freaked-out redhead tearing between lolling cattle and smoking buses, 70 pounds of stupidity on his back.

I rushed past the manager in the lobby up the stairs to my room, where I found the door locked, and the people inside unable or unwilling to understand my pleas to open the door. I went down to the lobby, where the manager greeted me with a concerned, vaguely bemused look.

“What’s happening, sir?”

“I need to get into the room. I left something in the room.”

“I’m afraid the room’s been let to another client, sir. What did you leave, may I ask?”

“I left some important papers.”

“Papers? What sort of papers, sir?”

“My passport. I left my passport in the room.”

He was older than me, probably around 40 or so. I remember his beard, curled up into the tight turban all Sikh men wear. I knew nothing about Sikhs other than that they had a reputation as shrewd but honest businessmen and for fierce loyalty. (But they were not to be taken for granted. Two of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s bodyguards had conspired in her assassination just two years previously. They’d been deeply offended when she ordered an attack on the Golden Palace in Amritsar, the seat of their religion.) This hotel manager was the first Sikh I’d ever met personally.

“Oh my, a passport is important, sir. Did you leave anything else in the room?”

It was at this point that I started to sense I was being tested—possibly by him, possibly by the universe. He was watching me closely. His eyes held a hint of amusement. I didn't sense cruelty, but I saw plenty of intelligence. There was no point in lying or getting confrontational with this man. My fate was well out of my hands. What recourse did I have? Call the Indian police and tell them I’d left all my money behind when I checked out? I could practically hear their laughter already, and who could blame them?

“Yes, I left some money in the room as well.”

“Money? How much money, sir?”

“All my money. … Fifteen thousand dollars.”

“Fifteen thousand dollars, U.S.! That is a lot of money, sir!”

He held my eyes for a moment, then reached under the counter and handed me the money belt. I unzipped it and looked inside. The stack of hundreds looked as thick as it had been the day before, next to my passport and credit cards. (When I counted it later, nothing was missing.)

“Do you understand how much money this is in India, sir? One could buy this hotel and several others like it.”

“Yes, thank you. I understand. I can’t believe I did this.”

“The boy who cleans the rooms found your possessions. He brought them to me. This boy earns about ten dollars in a month’s time.”

I pulled out a few hundreds and said, “Please give this to him, with my thanks.”

“Oh no, sir, that would insult him.”

“What can I do then?”

“Give me three hundred rupees”— about $15 at the time—“and I’ll have a party here with the other employees to honor him for his noble action. That will be the thing to do.”

“Are you sure?”

“I am sure, sir. Now, go while you can still catch your train. And sir, please be more careful with your possessions.”

I shook his hand, thanked him, and ran back to the train station, where I immediately faced the challenge of finding my place in the surging rolling city that is an Indian train. It wasn’t until hours later that I had a calm moment in which to think about what had happened that morning, and it wasn’t until years later that I understood that I’d almost become someone else.

You see, that stack of hundred dollar bills ultimately carried me through several years of travel in India, Nepal, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, Greece, France, Holland, East and West Germany, Czechoslovakia and back to New York. Along the way, I came to see myself, and at least imagined that others saw me, as a guy who could step out into the unknown and keep his balance. A savvy traveler. An experienced, tested adventurer. A guy who could handle himself. Let’s be honest: the kind of guy Katalina Montero Alverez might admire. This became a central thread in my life story, a pillar in my identity. Now, more than three decades later, I’m still comforted and protected by that narrative, by that self-image. I consider it my own, something I worked hard for.

But the truth is that this life of mine was a gift from a Sikh man in Old Delhi whose name I never asked on a hot, humid November morning in 1986.

Chris Ryan is the host of the Tangentially Speaking podcast, and the bestselling author of Sex at Dawn and Civilized to Death. Learn more at chrisryanphd.com.