My First Attempt at River Surfing in Montana

I imagined that Missoula surfers would be a tough crowd. It's a blue-collar hunting town, after all. Perhaps a bunch of hillbillies would pull guns on me, fire shots at my feet and command me to "Dance California, dance!" So I'm a little taken back when I arrive at the river wave and see men and women of all ages cordially massaging each other’s shoulders as they wait in a conga line.

Maybe I imagined that last detail, but it was a friendly crowd.

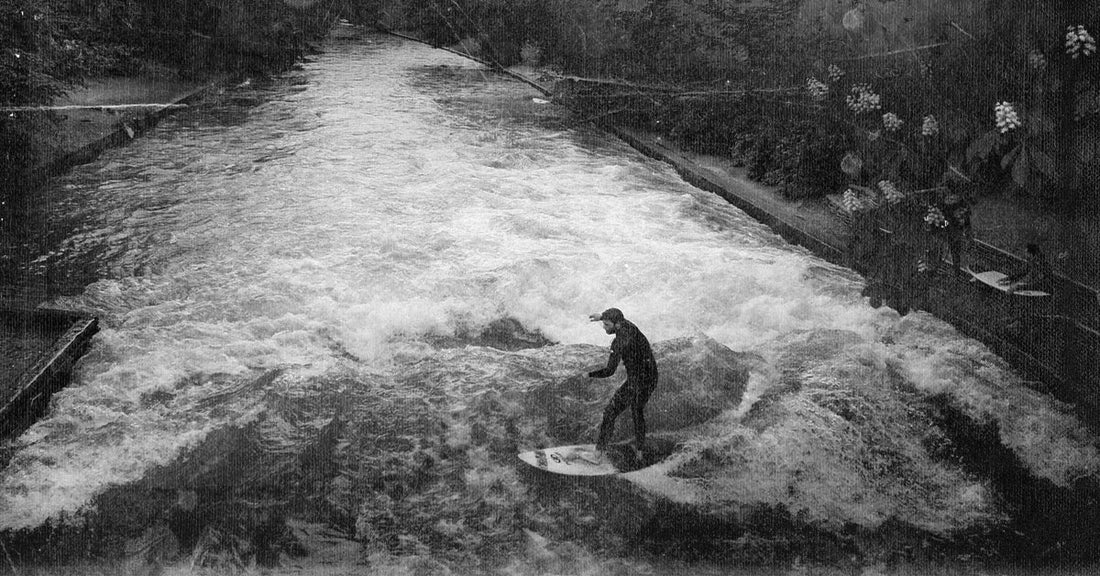

The wave is called Zeros, and it's under a freeway overpass just outside of Missoula, Montana. Cement pilings have been driven into either side of the river and the valley echoes when trucks go past. About a dozen surfers wait in line. They wear full wetsuits and strap their leashes just below their knee (instead of to their ankle, the way most surfers do). Their leashes also have special pull-away cords designed for big-wave surfing, in case a surfer needs to ditch their board in a hurry. This delightful situation can arise if a surfer's leash gets wrapped around a rock and the force of water is too strong for them to undo the velcro. I eye the river, terrified at the thought of my leash wrapping around a submerged rock. It's not so much drowning that scares me—it's that I will have died while surfing a waist-high wave.

The wave breaks where the banks move toward each other in the shape of a V. The squeezing of the river walls creates what's known as a wave train, a series of breaking rapids down the center of the river. "You want to get the first wave in the train," a local named Ian Stokes tells me. I watch him jump from the bank, ferry across a couple of seams of whitewater on his stomach, and, when in the center of the rapid, pop-up and slash the flowing canvas.

Stokes lets me borrow his board. When I’m at the front of the conga line, I jump off the bank and am promptly swept down the river like a leaf. I swim hard for the shore. The bank is full of slippery cobblestones and cement chunks that cut my feet as I flounder up the shore like a baby giraffe on an ice rink.

I return the board to Stokes feeling just the littlest bit defeated. He turns it over and one of the fins is missing. I’m sure he's going to shoot me. Instead, Stokes shrugs about the fin and says that he has a replacement in his car.

I try a few more times unsuccessfully then begin to get the hang of it. Perhaps the strangest part of surfing a river wave is the view. When I finally muster the confidence to unglue my eyes from the nose of my board and look upstream, I see a powerful river rushing toward me, yet I am standing in place. It’s as if I’m breathing in my visual field. For a moment I feel as if I’ve miraculously found some loophole in physics. Then I catch an edge, the river has its way with me, and I am reminded that science is real.

Rather than tracking tides, wind and swell, Missoula surfers use their own forecasting technology. The main factor is snowmelt. If warm nights are forecasted, surfers know that there will be an increase in snowmelt, and new rivers could open up in the following days.

I ask Stokes if he surfs all year long. "When chunks of ice start flowing down the river," he says, "that's when it's time to stop.”

Montanans take a sadistic pride in their durability. When the river becomes too dangerous to surf, they pivot to more relaxing pastimes such as ice fishing, also known as recreational hypothermia. If ice fishing becomes too monotonous, they trudge up the snow-covered mountain to hunt elk, a side arm at their hip in case a mama grizz is looking for a snack.

After the session, we walk up the path into a dirt parking lot for a barbecue. I feel like I'm in the twilight zone. These guys dress (and speak) like surfers, but the nearest ocean is two states away. One guy wears board-shorts, sandals and a backward hat. Another peppers words like "sick" and "gnarly" into his lexicon without any sign of awkward effort. They don't speak with the nasally, slightly bewildered accent of some California surfers, though. Montanans speak in lower octaves and end their statements with more self-assuredness. The tailgate party is nearly identical to the ones I grew up going to in Santa Cruz, down to the beer, shit talking, and Coleman barbecue on the back of a rusted black Tundra.

The Missoula surf scene is new. It’s a beautiful thing, the liminal stages of surf culture. There’s no legacy, ego or established industry. It’s just for fun. As I drive away, I tell them to give me a call if they ever make it to Santa Cruz, and they send me off with shakas and elk steak.

By Kyle Thiermann

Check out Kyle’s podcast here

Image by: Mark McGregor