Back in 2007, Reilly C. kicked every day off at the edge of a snowy Telluride mountain. “I lived to be knee-deep in powder, but skiing aside, I chased anything adventurous,” says Reilly, a reporter who’s asked to use his first name in accordance with his AA program. "Ten-foot cliff drops, skydiving, climbing volcanoes in Sumatra—you name it.”

When a friend of his returned from an ayahuasca retreat in Peru and recounted his profound experience, the adventurer in Reilly saw potential for a new kind of voyage: one within the mind.

Ayahuasca is a hallucinogenic tea from the Amazon observed as a sacrament for intentional healing, but Reilly candidly expresses that his intention at the time was just to see fun visuals. “Looking back, I do believe that on some level I was looking for healing,” he says. “My friend credited it for healing his depression. But consciously, I just thought it would be fun.”

Reilly got just what he had hoped for: Multidimensional fractal patterns danced across his closed eyes for hours as he laid in a group ceremony led by a facilitator. He returned to ayahuasca a few more times over the years and began to see subtle shifts in his lifestyle as a result. The most significant change came years later: A heightened awareness of his drinking habits.

Returning to the Roots of Addiction

The small-town mountain lifestyle of Telluride, Colorado, which Reilly called home, revolved around a heavy drinking culture. It wasn’t until he had a few ayahuasca ceremonies under his belt that he realized it wasn’t normal to regularly wake up struggling to recall the night before.

He recognized the behavior fell in line with a 1,000-year lineage of Irish-Catholic alcoholism. “My friends and I were all just creatures of culture,” he says. His drinking worsened when he switched to work remotely in 2012. Days spent alone and the blurring of work hours with home life led him to drink earlier and earlier. “It got to the point where I started reaching for beers at 10 a.m..” This pattern isn’t uncommon, as rates of alcohol use disorder worsened when the workforce was home during the pandemic. By 2013, his drinking habits had already cost him his relationship and landed him in jail. It was around that time that a simple question cut through his mental chatter during an ayahuasca ceremony: “Why do I drink?”

That moment set Reilly on a healing journey. But while he credits psychedelics as the catalyst, he says Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and long-term lifestyle changes are how he has maintained sobriety. There was one hitch in his AA participation, however: It required abstaining from all substances, including psychedelics. Reilly wasn’t willing to give up psychedelics, which had proved to be valuable healing tools for him. As a result, he felt he couldn’t show up as his full self during AA meetings.

Psychedelics in Recovery

Reilly was not alone. After finding an understanding sponsor, he realized that there must be others in AA who believe psychedelics to be a healthy, valuable part of their recovery. An online search led him to discover Psychedelics in Recovery (PIR), a national group for people in 12-step programs who also have an interest in psychedelics and/or plant medicines as an aid to recovery. PIR now hosts over 20 online Zoom meetings per week and three or four in-person meetings per week nationwide. Reilly leads his local chapter.

But how can one drug help heal the substance use disorder of another? Nearly every expert will sum up the potential for psychedelics to treat addiction in one word: community. Addiction therapist Tessa Vita Levine is quick to reframe how we view substance use disorders in the individualistic versus community context. “What if we looked at people who develop substance use disorders as wise humans who are, on some level, intuitively reaching for healing?” she asks. Instead of viewing substance use as inexplicable self-destruction, we can reframe it as a person who is looking to heal with a substance but lacks the context to make it effective. This introduces a more compassionate approach that could be key in recovery.

“So much of addiction is driven by loneliness,” says Reilly. Western medicine, much like its culture, is highly individualistic. Indigenous cultures have strong community infrastructures that define how they approach all matters of society, including healing. This has allowed them to successfully steward psychedelic medicines for centuries at low costs with little risk. The West has struggled to do the same.

Indigenous Approaches to Healing

Dr. Jeeshan Chowdhury, MD, founded Journey Colab, a psychedelic drug development company that holds these Indigenous community values at the core of their strategy. Rather than pinning down a scientific mechanism of action to support anecdotal stories, Chowdhury urges people to respect the complexity of addiction, particularly as it is shaped by relationships. Both Reilly and Chowdhury steer any topic around psychedelics back to the community ethos. Journey Colab is centered around equal access, inclusion and giving back. Instead of aiming to modernize Indigenous healing practices, they uphold their values as the core of their work.

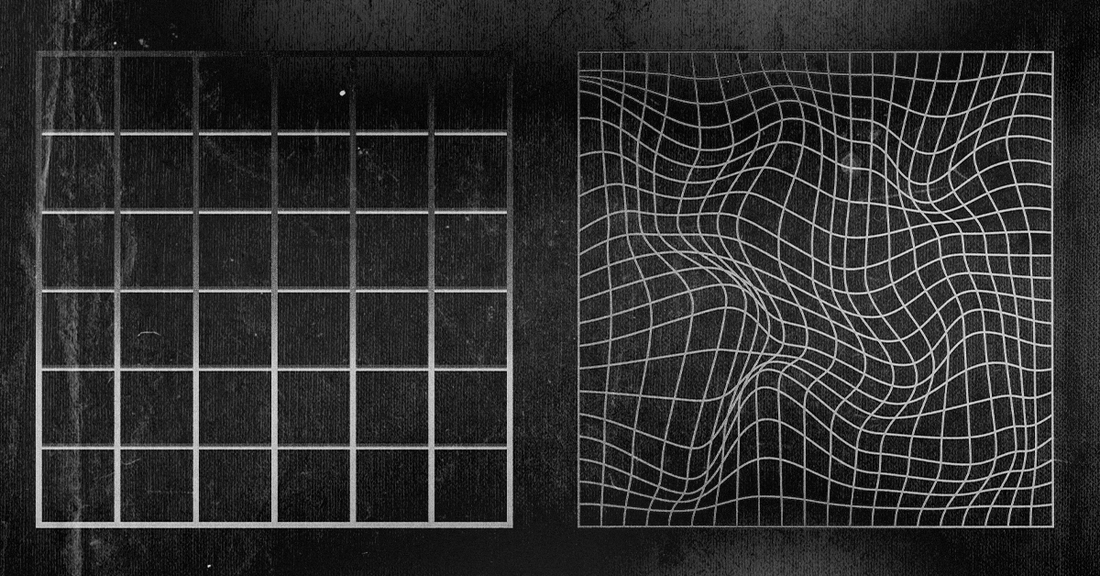

To connect the power of community with science, turn to the well-documented relationship between psychedelics and neuroplasticity. Neuroplasticity is how the brain changes through growth and reorganization of neural networks. Psychedelics have been shown to promote neuroplasticity, but that’s not just a chemical process. Studies consistently show that the environment can make or break psychedelic healing potential.

Indigenous wisdom further connects to modern science when we look at the “critical period.” A critical period is the relearning rate measured in psychedelic research studies, which is correlated to the length of the psychedelic experience. Chowdhury points to Native Americans and their work with peyote. Peyote is a cactus which contains mescaline, a psychoactive compound known to last nine to 12 hours (significantly higher than other psychedelics). If there’s a longer “critical period” during a longer psychedelic journey, a mescaline trip may provide a more durable healing response.

To protect the ecological conservation of peyote plants, Journey Colab is developing a synthetic derivative of mescaline to treat alcohol use disorder in group therapy. There is a deep understanding that psychedelics are powerful tools for addiction recovery, but they are just one part of the toolbox.

Read More: Why We're (Still) Taking a Stand for Psychedelics

Read More: Why We're (Still) Taking a Stand for Psychedelics

Tobacco is a perfect example of how a plant’s healing properties can be twisted by extractive capitalism. Traditional tobacco is considered to be one of the most powerful psychoactive plants in the world. It has been used as a medicine of spiritual importance for centuries, but the West had a different translation. The “more-is-more” culture took a plant meant to be used sparingly and with reverence in community settings and scaled it to the point where it not only lost its medicinal benefit, but actually increased its addictive potential.

“If psychedelics are legalized and end up in vending machines next to cigarettes, will we be opening up our communities to fall apart again?” Reilly muses. To truly unlock the healing potential of psychedelics to treat substance use disorder, we don’t just need policy reform or FDA approval. The psychedelic renaissance needs a concurrent paradigm shift in how we view medical treatment, addiction and society. Psychedelic use as an aid to recovery can destigmatize our worldview on drug use and in turn, how we look at one another—a much-needed change.

Dorna Pourang is a psychedelic researcher who sits on the MUD\WTR and Trends w/ Benefits’ Advisory Board. She launched the veteran program at The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) and her research has been published in the Journal of Neurological Surgery, American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, and AJCM. You can find Dorna on LinkedIn and Instagram.

Read more: Waves For Water Founder, Jon Rose, Opens Up about PTSD

Read more: Talking to Kids about Psychedelics

Read more: Healing with Psilocybin