“Mold experience into stories as a mnemonic device. Travel is a chaos of experience, momentarily memorable and distressing in its capacity to flee the mind and disappear without a trace.”—Tim Cahill

Many years ago, Tim Cahill was on a hilltop in Virunga National Park, surveying a troop of endangered mountain gorillas, when an old football injury caused his knee to pop out of socket. “Clutching my knee to my chest had the effect of turning me into a human bowling ball,” he later wrote, “and I began rolling faster and faster down the steep and grassy slope.” The gorillas scattered. Cahill worried that the researchers who’d brought him to the Congo might scold him for disturbing its wildlife. Instead, they commended him for being the first known human to charge a troop of mountain gorillas, albeit unintentionally. “And that,” Cahill wrote, “is how playing football very badly can lead to important scientific discoveries.”

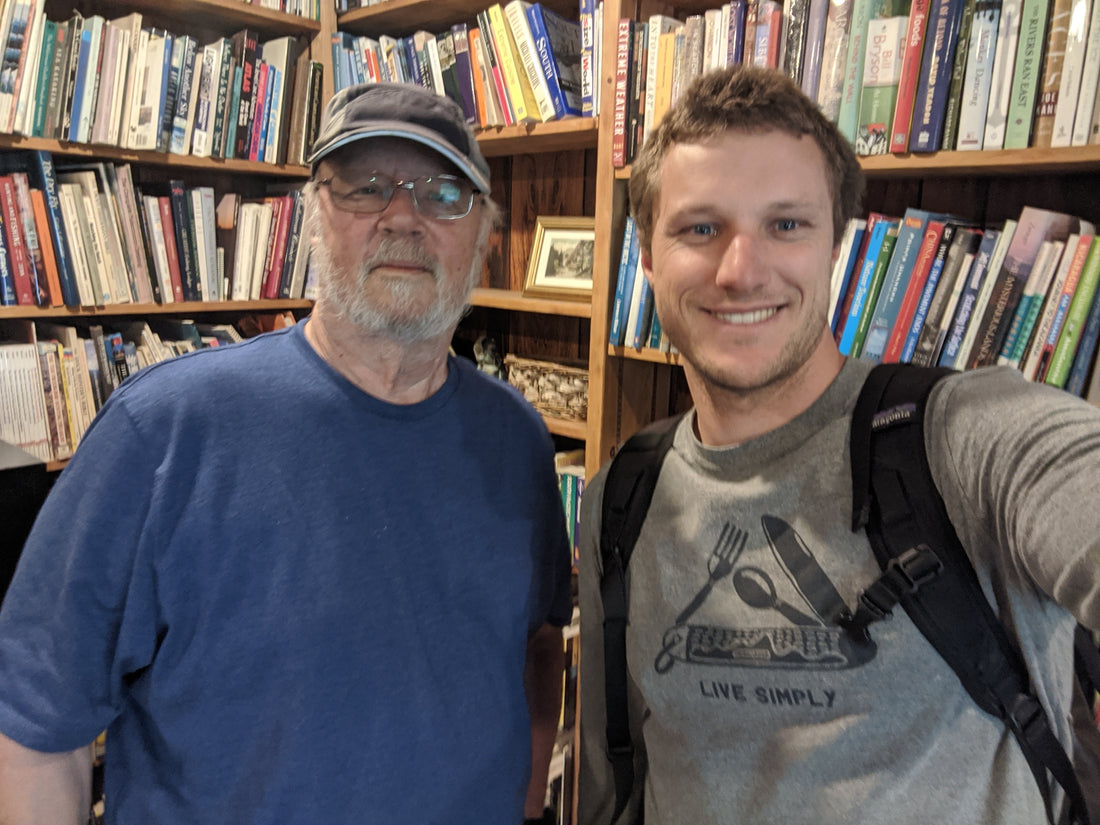

I am interviewing the 76-year-old co-founder of Outside magazine at his home in Livingston, Montana, population 8,000. He has spent more than half a century exploring wild places, relishing in his folly along the way. By positioning himself as self-deprecating rather than heroic, he gave a generation of “non-adventurers” permission to strip down and jump into icy water, as Cahill himself once did at the North Pole.

Going on an adventure doesn’t require bulging calf muscles or an L-shaped jawline, but it usually does require a particular narrative about yourself. You need to believe that you are the type of person who can make it through a blister or a chilly night without collapsing into the fetal position, shooting a flare, and calling for the chopper. Cahill was a tad overweight, could often be found at the pub, and although he was a dedicated conservationist, he loathed sanctimony. If there is an Anthony Bourdain of the outdoors, Cahill might be it. “If I have a legacy,” he said, “it's giving people back their dreams.”

“Was there a moment when you realized that making fun of yourself was a superpower?” I ask. He recounts dreaming up the idea for Outside with his co-founders in 1977. Cahill argued that people didn’t want to hear about adventure from the perspective of fearless experts. “Superman is no fun as a story,” he recalls telling them. “He can leap tall buildings in a single bound, but what’s this mountain gonna mean to him? We need somebody who can write a coherent English sentence, who is easily frightened, and who’s a bit of a doofus. Put that guy at the bottom of the mountain, and we’ll have some drama.” His cofounders looked at him and said, “OK, Tim, give it a try.”

Although Cahill was raised Catholic, he describes his current status in the Church as “long-lapsed.” He seems to draw a deeper sense of spirituality from story, and he writes about it with the same reverence others reserve for God:

In my mind, I have always envisioned a blinding curve of energy, a great story arc in the sky. … Sometimes I wake up at my desk and realize that I’ve been working for three hours. But it feels like it was 30 minutes. I think I went somewhere for a while and consulted the Great Story Arc. It was there that the stories of our history on Earth lit me up and informed the best of my writing.

Cahill seems cool with how his life turned out, and he remembers it better than most. During our interview, he answers each question with a story that is rich in detail and humor. Experience is notoriously ephemeral, and even the most vivid memories tend to recede like an old man’s hairline. But Cahill has spent his life scribbling down the chaos of travel into notebooks, then organizing them into stories. As a result, he has a deep Rolodex of tales. When working as a travel journalist, he made a habit of writing his external observations on the left side of the notebook while reserving the right for internal reflections. If I did the same, my own notebook would look like this: (Left side) The Columbian woman had hazel eyes and jet black hair resembling the Rio Guaviare under the moonless night sky. (Right side) Her presence alone brought forth my inadequacy, and I felt myself shrivel like a snail.

After the interview, we climb in his Jeep and go to lunch. Standup comedy plays on the radio and dirty paw prints speckle his backseat. A few blocks from his house, we eat sandwiches on a picnic table while looking at the Yellowstone River. I show Cahill a video of me surfing big waves in a reaching attempt to earn his respect. The video prompts him to ask if I have ever heard about the time he died. I haven’t. A few years ago, just after his 71st birthday, he boated through the Grand Canyon with friends, most half his age. They hit a section of notoriously dangerous rapids and he was flung from the raft and pulled deep underwater. He described the incident in an article he wrote for Outside:

The river seemed to yank me directly down as if by the feet, and I was looking up through about 15 feet of water at what appeared to be a perfectly still round pool, colored robin's egg blue by the cloudless Arizona sky.

Cahill made it to the beach, but he had inhaled a lungful of water. He collapsed on the sand and his heart stopped for four minutes while his friends performed CPR. Finally, he awoke, disoriented and swinging at his saviors before realizing what had happened. He was airlifted out, then returned the following year and successfully completed the trip. During the minutes that he was dead, he recounts seeing nothing on the other side. No bearded man. No relatives. No blinding light of unconditional love. Nothing.

“Fuck,” I think, “is it possible that this is all there is? Then the cops show up and the party’s over?” The thought gives me just the tiniest bit of existential dread. I identify with the way Cahill has traversed his life in the outdoors, seeking adventure to understand himself better and using writing as the tool to recount his experiences for others to enjoy. It occurs to me that of all the floors in the hotel of consciousness, my penthouse moments have been less about the places I have been and more about the vividness with which I was able to notice the details. Cahill finishes his story and gazes out at the Yellowstone as a question comes to me. It’s something I feel a strong need to know.

“When you were underwater,” I ask nervously, “did part of you know that if you lived, it would be a great story?” He looks at me a little perplexed and says, “Of course.”

Listen to the full conversation with Tim Cahill here.

By Kyle Thiermann